Background

As a docent at the Howard Steamboat Museum and someone with an affinity for Episcopal churches, I was curious about the church located a few blocks from our museum, which we knew that Howards once belonged to. I hoped that a trip to the church would give me a glimpse into the religious, social, and philanthropic lives of the Howards. I satiated my curiosity by requesting a visit and tour and friendly staff at St. Paul’s was to happy to oblige. On August 5th, 2021, I toured St. Paul’s and was given a in-depth tour by their senior warden, Walker ‘Sonny’ McCulloch. Sonny is a lifelong member of St. Pauls with ancestors who have attended the parish since the 1850s. He is a living repository of knowledge of St. Paul’s history and was acquainted with Loretta Howard in her later years

St. Pauls: A Brief History

Organized in 1836, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church is intertwined with the Howards and has many parallels to our museum. The Episcopal Bishop Jackson Kemper founded the parish and many others as a missionary bishop to the expanding western frontier. Bishop Kemper was fond of ‘Christ Church’ and ‘St. Paul’s for his church plants and thus, many Episcopal parishes along the Ohio River have one of these two names. (McCulloch, personal communication, Aug 5, 2021). In fact, there are four churches in greater Louisville named St. Paul’s or Christ Church!

History of St. Paul’s, Sonny McCulloch (4 min.)

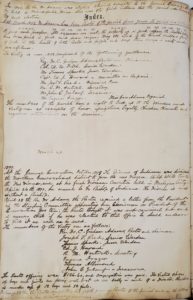

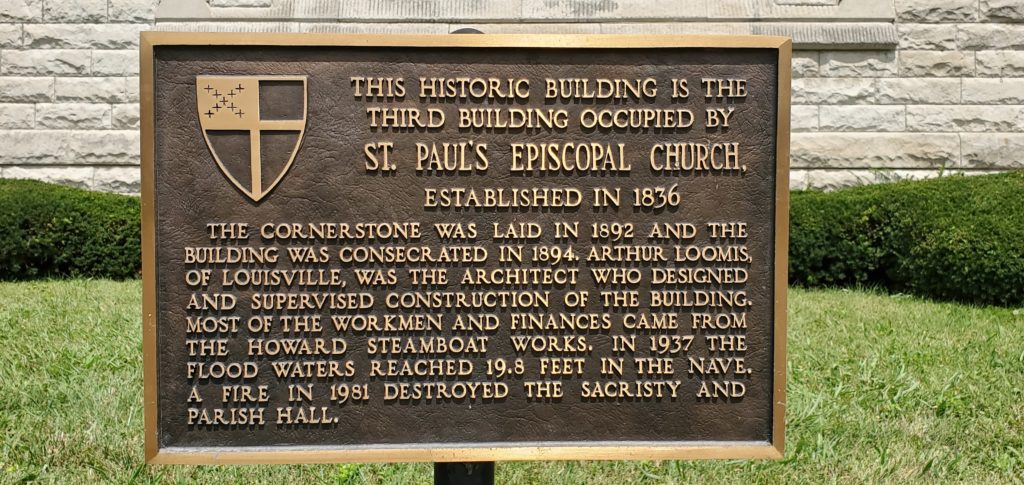

While much of St. Paul’s historical documents were lost to the 1937 flood, a Parish Register documenting the first 60 years of the parish was salvaged. There are no records of James and Rebecca Howard involvement at St. Paul’s, but it is likely that as recent English immigrants, they were members of the Church of England (Anglican Church), and its later American counterpart, the Episcopal Church. The register does indicate that Captain Ed. J. Howard was a member of the vestry in 1898 (a position similar to non-profit trustee) and several historical sources corroborate his instrumental role in building the current sanctuary, which has stood in its current place since 1893.

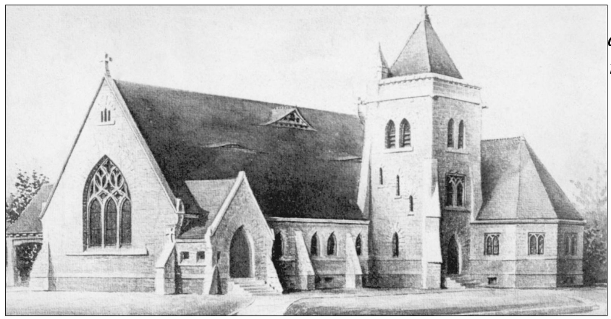

(Click image to enlarge)

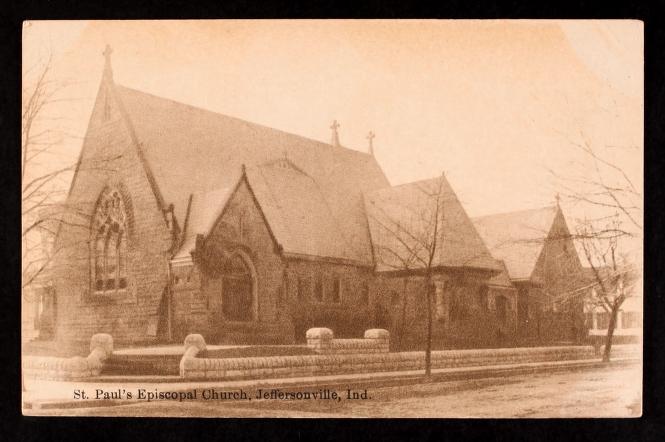

The church purchased the land and laid the cornerstone for its parish hall in 1892. The parish hall was used for worship until the sanctuary was completed in 1893. Capt. Ed Howard served as the contractor for the church while building his own mansion and managing the Howard Shipyards, an incredible feat!

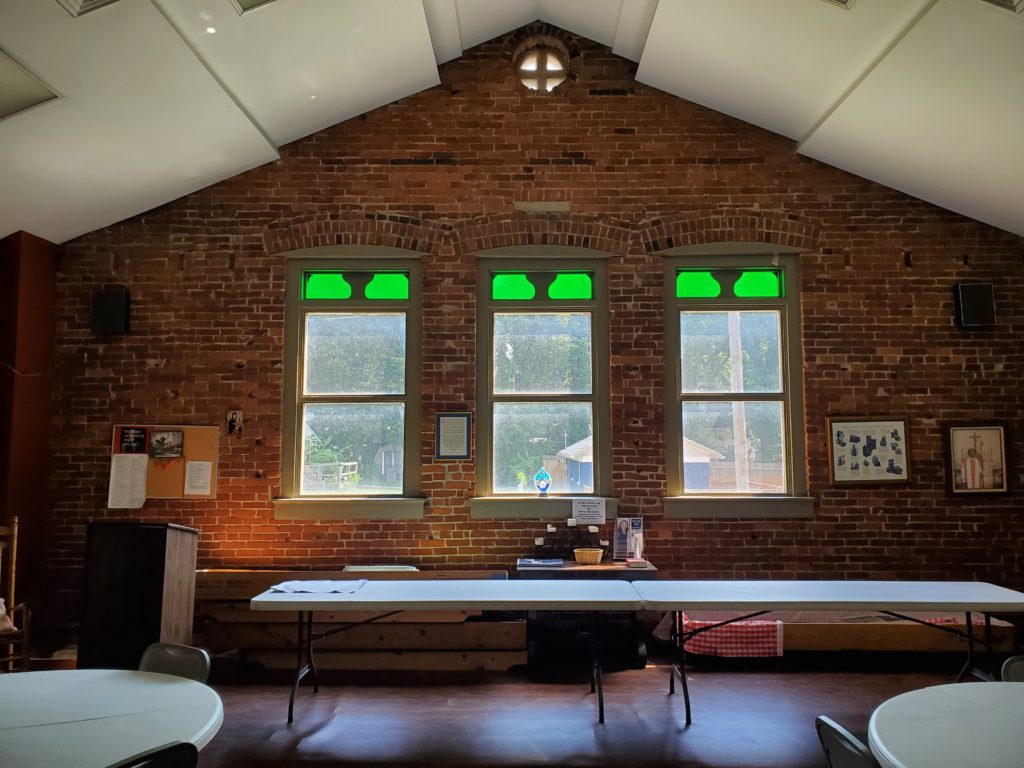

Like the Howard mansion, the church has survived both flood and a fire. The church was submerged in flood waters of 1937, but the floors did not warp or rot. The current floor is the original 1894 floor (albeit with a few creaks and character from years of use). In 1981, an electrical fire engulfed the parish hall and sacristy (storage closet for clerical garments), with smoke damaging the nave walls and heat that destroyed the original organ. This rear part of the church had to be rebuilt in 1981, while the original exterior wall from 1892 was retained.

Members of St. Pauls took the church’s woes in stride and joked that their church was the ‘James Taylor church’ since like the song lyric, it had ‘seen fire and rain’. They restored the church to its Victorian-era glory in 2010 and crowd-funded the installation of a pipe organ in 2012. Their creative fundraising effort was recognized by James Taylor himself. He raised money through a charity auction of the orchestral score of ‘Fire and Rain’ and donated the bids to St. Paul’s so they could install a pipe organ (‘James Taylor Church’, 2021).

Gothic Architecture with a Steamboat Twist

Architectural choices in church buildings often convey the cultural and theological zeitgeist of a denomination and its members. St. Paul’s is no exception. The Episcopal Church and its mother church, the Church of England, rediscovered their catholic, pre-Reformation roots in the mid-to-late 19th century (Stanton, 1997, 11), the time when St. Paul’s sanctuary was built. The revival of late medieval Christian beliefs and practices paralleled the Gothic Revival in church architecture This style was so popular that other Protestant denominations adopted it in their parish-building efforts around the same time (Baresel, 2020).

Famed architect Arthur Loomis, who designed the Speed Museum, the Conrad-Caldwell House, and many other prominent Louisville edifices, proposed a new Gothic church sanctuary. The original plans submitted by Loomis included a bell tower that was never completed due to lack of funds (Nokes, 2002, 48). Instead, the portico became a small chapel and columbarium. Ed J. Howard served as the contractor for the church and its rectory (house for the parish priest or ‘rector’) (Baird, 1909, 235). Using steamboat workers, the house and rectory were built promptly for the sum of $14,466.66 (Baird, 1909, 234). Capt Ed. himself contributed $500 to this church building and his contracting skills saved the church around $2,000 in initial costs (Baird, 1909, 234). The rectory was built in December 1894 in a matter of one month (W. McCulloch, personal communication, August 5, 2021), a testament to the efficient and skilled work of the Howards’ laborers.

The church bears witness to the Howards’ signature craftsmanship and steamboat carpentry. The hammerbeams, or decorative roof beams, at St. Paul’s are ornately carved with quality wood, not unlike cabin arches found in Howard steamboats. Both hammerbeams and cabin arches provide structural support while enhancing the aesthetics of the ceiling. Standing at the altar, one notices that the floor gently slopes from the entrance to the front. This is not incidental, but a feature on steamboat decks as well. The ceiling resembles the hull of a boat. It is not hard to fathom that Howard workers could build a sturdy church roof from their experience in building boat hulls. In fact, the congregational seating area of cathedrals is called the nave, from the Latin word for boat.

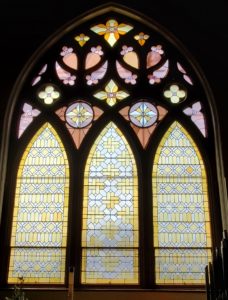

The window at the rear of the nave epitomizes the Gothic Revival style. The geometric tracery (frames around the panes of glass) are traditional medieval style, but the biblical scenery in rich hues of the original Gothic period was replaced with pale geometric designs to allow in more natural light (McNamara, 2011, 224). Medieval stained glass windows served as “textbook of the illiterate” (McNamara, 2011, 224) a didactic tool to help clergy teach uneducated parishioners the stories of the Bible. In contrast, 19th century churchgoers were largely literate and needed more light to read from prayer books and sing from hymnals.

If you pass by the church on Market St., you will see a plaque commemorating the current congregation and the contributions of the Howards’ workers. St. Paul’s in Jeffersonville remains one of the best preserved Gothic revival churches in the greater Louisville area.

Fond Memories of Loretta Howard

Mr. McCulloch and his family have been friends and acquaintances of the Howards for several generations. Sonny’s grandfather was mayor of Jeffersonville and dined with the Howards on occasion. Sonny got to know Mrs. Loretta Howard as she frequented the service station that his father owned. On one occasion in the late 1950s, Mrs. Howard invited Sonny to the museum and gave him a tour. Loretta is fondly remembered for her warmth and vitality even in her later years.

Memories of Loretta Howard, Sonny McCulloch (2 min)

Looking Forward to the Future

St. Paul’s remains an active worshiping congregation 185 years after its founding. Mr. McCulloch recounts that a passerby many years ago referred to St. Paul’s as a ‘miracle church’ since it has survived many challenges and changes (W. McCulloch, personal communication, August 5, 2021). You can learn more about this ‘miracle church’ by visiting http://www.stpaulsjeff.com/ Their website contains ample information for the history aficionado and prospector visitor alike!

References

Baird, L. C. (1909). Baird’s history of Clark County, Indiana. Indianapolis, IN: B.F. Bowen & Company.

Baresel, J. (2020, August 27). As we build, so we believe: Gothic architecture’s place in the American liturgy [Blog post]. Adoremus. https://adoremus.org/2020/08/as-we-build-so-we-believe-gothic-architectures-place-in-the-american-liturgy/

Kramer, C. E. (2007). This place we call home: A history of Clark County, Indiana. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

McNamara, D. R. (2011). How to read churches: A crash course in Christian architecture. London: Herbert Press.

Nokes, G. J. (2002). Jeffersonville, Indiana. Chicago: Arcadia Publishing.

Stanton, P. B. (1997). The Gothic Revival and American Church Architecture. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. (2021). The James Taylor Church. St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. Retrieved August 10, 2021, from http://www.stpaulsjeff.com/we_are_the_james_taylor_church